Freeport CEO may be ready to sell, but are there any buyers?

Freeport-McMoRan Inc.’s annual LME Week party is usually an opportunity for Chief Executive Officer Richard Adkerson to hobnob with the traders and consumers who buy copper from his mining company. At this year’s event, he was surrounded by investment bankers.

We are probably not going to see massive M&A from the majors in the next 12 months.

With its biggest stock overhang — a deal around its flagship asset in Indonesia — close to being solved, the miner has said all options are open, even potentially a sale of the entire company. The comments will have everyone running the numbers. The question is, who would want to buy it?

Major miners, including Rio Tinto Group, have said they’re keen to boost production of copper, the industrial metal that’s benefiting from demand for new energy systems and rechargeable batteries. But with many companies still battle-scarred from previous debt-fueled acquisition sprees, and trade tensions threatening global growth, analysts say making a play for the world’s largest publicly traded copper producer would mean swimming against the tide.

‘$20 billion plus’

“I’m not sure there is a buyer for large-scale assets at premium in the market now,” Christopher LaFemina, an analyst at Jefferies LLC, said in a phone interview from New York. “Even though they all want copper, who’s going to spend $20 billion plus?”

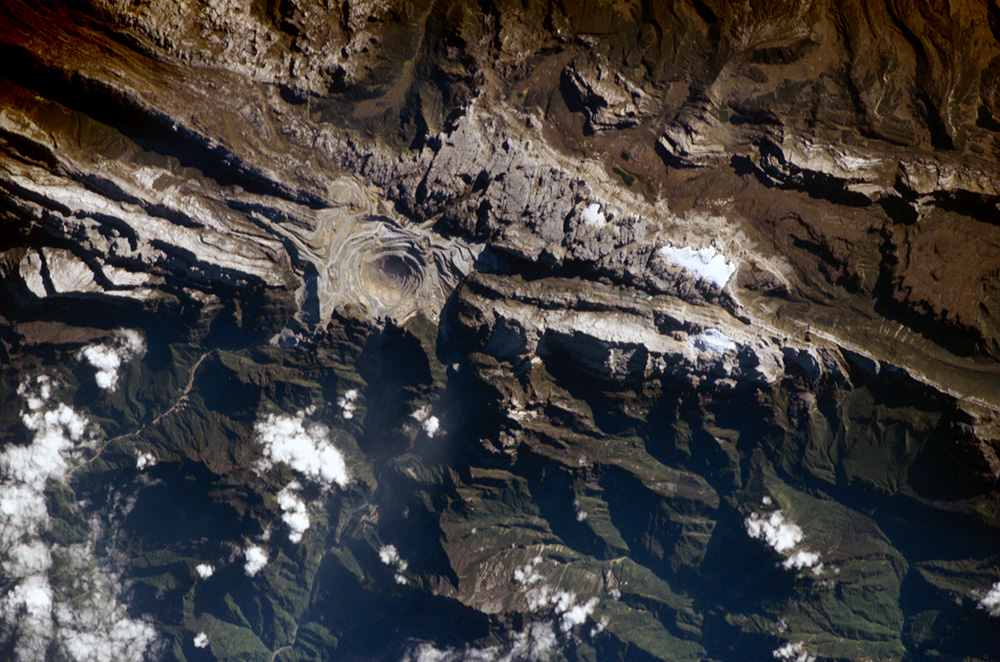

Freeport is in the final stages of multi-year negotiations to divest a bigger stake of its copper-and-gold mine in Indonesia in exchange for a new contract to operate Grasberg into 2041. Years of uncertainty over ownership of the giant mine have made the company difficult to value and its stock volatile, leading to speculation about Freeport’s future once it’s resolved.

There are multiple ways buyers could approach Freeport with the aim of growing their copper portfolios, including forging partnerships, buying individual assets, or trying to swallow the entire company.

In a recent interview, Adkerson, 71, made it clear all options are open, and said if a full-takeover offer emerged that was good for shareholders, the Phoenix-based company would not try to block it.

But Jeremy Sussman, an analyst at Clarksons Platou Securities Inc., says it’s too soon for that kind of play. “Failed acquisitions of the past are still front and center in management’s eyes,” Sussman said by phone.

“The mentality among the major miners continues to be one of austerity,” LaFemina says. “If it’s not broke, don’t fix it.”

Freeport’s enterprise value to Ebitda ratio, a gauge of valuation, has fallen in the past year versus the comparable copper prices, suggesting the company is undervalued. LaFemina estimates fair value for the full company — which had a market capitalization of $18.4 billion at the end of trading on Tuesday — to be about $34 billion.

Of that, Freeport’s post-divestment share of Grasberg is worth about $10 billion, he said. Given the complexity of the Indonesian mine and it’s environmental footprint, LaFemina doesn’t think any other publicly traded company would want to own Grasberg — Rio is already divesting its own stake as part of the broader deal — though Chinese buyers might.

Freeport slipped 1.2 percent to $12.53 at 11:49 a.m. on Wednesday in New York.

‘Logical approach’

While Freeport has no plans to sell its Indonesian operations, it wouldn’t stand in the way of a deal that made sense for all parties, Adkerson said in the Oct. 4 interview. State-owned PT Indonesia Asahan Aluminium has a Right of First Offer for Grasberg if a buyer emerges who doesn’t have experience in underground mining. If that happens, Freeport would help establish a good relationship between the buyer and the Indonesian government to ensure everyone a smooth transition, he said.

“The logical approach would be to split the company between Grasberg and everything else,” LaFemina said of Freeport. “But even then, who buys everything else?”

Freeport’s remaining mines are all in the Americas. The most significant assets are a 54 percent stake in the Cerro Verde mine in Peru, a 51 percent stake in El Abra in Chile and a 72 percent stake in the Morenci mining complex in Arizona. Those operations already include, to varying degrees, partnerships with Sumitomo Metal Mining Co., Cia. de Minas Buenaventura SAA and Codelco.

Regularly approached

The company is regularly approached about partnerships, including by Chinese companies, and Rio is also interested in “looking for opportunities to partner with us,” Adkerson said in the interview.

Rio is keeping watch on a list of potential options to boost its copper portfolio and has the balance sheet strength to pay a premium if needed, CEO Jean-Sebastien Jacques said in an August interview. The producer made a thwarted approach to add the giant Collahuasi operation in Chile during the 2015 commodity slump, according to people familiar with those talks, and Jacques told investors on a February earnings call he keeps a “Christmas list” of four or five key assets.

Debt could also be an issue for a potential buyer. Like most of its peers, Freeport sold assets in the last downturn to slash debt. At the end of the second quarter, total debt was a little over half the level five years earlier, but still more than $11 billion.

Faced with that, there needs to be a clear reason to pull the trigger, LaFemina said.

“The industry has to be rewarded for growth before deals of this scale would happen, and that’s not the case in the market today,” he said.

(By Danielle Bochove)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments