Over 25% of global copper supply trapped by ESG roadblocks — study

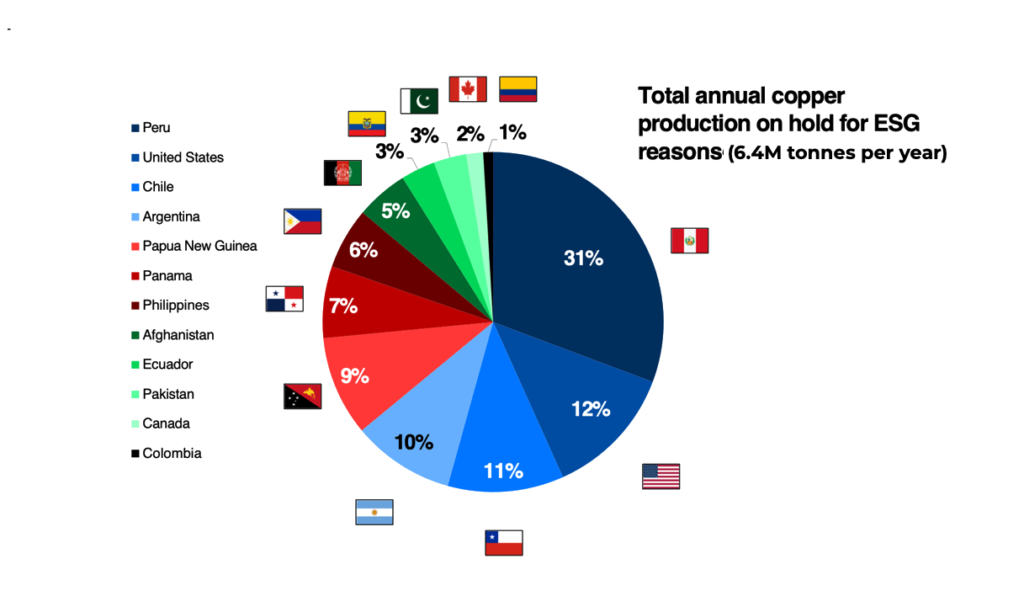

About 6.4 million tonnes of copper production capacity, equal to more than 25% of global mine output, is stalled or suspended due to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues, a new study shows.

These bottlenecks, unlike geological or technical barriers, stem from conflicts that could be resolved through stronger governance, deeper community engagement, and more sustainable practices, according to analysts at GEM Mining Consulting. The findings come as demand for copper continues to surge, driven by electrification, renewable energy growth, and the digital economy.

Countries including Chile, Peru and the United States hold some of the largest copper reserves now off the market. Unlocking even a fraction of these projects could ease looming supply shortages during the energy transition, Patricio Faúndez, head of economics at GEM, says.

Peru accounts for the largest share of untapped copper, roughly 31% or 1.8 million tonnes annually, followed by the US with 0.8 million tonnes, Chile with 0.7 million tonnes, and Argentina and Papua New Guinea (PNG) with about 0.6 million tonnes each.

Peru’s halted output nearly matches its current annual production. If released, the country could reclaim its position as the world’s second-largest copper producer, surpassing the Democratic Republic of Congo with more than 4 million tonnes per year, the study notes.

In the US, restarting suspended projects could narrow the gap between domestic production and rising consumption, strengthening supply security and reducing import dependence.

In Chile, the stalled copper could finally break a decades-long production ceiling of around 5.5 million tonnes per year, pushing output beyond 6 million tonnes and reinforcing the country’s leadership in global supply.

Three telling cases

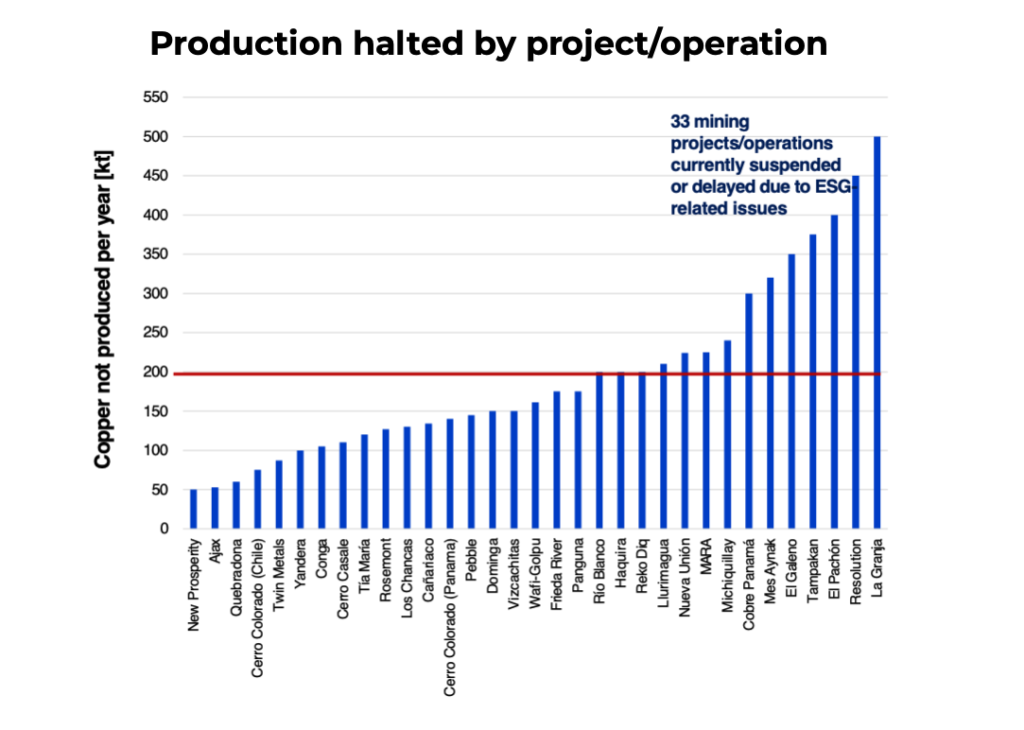

Among the 33 projects paralyzed by ESG factors, three stand out: La Granja in Peru, Resolution Copper in the US, and El Pachón in Argentina.

La Granja, owned by Rio Tinto (ASX: RIO) and First Quantum Minerals (TSX: FM), has faced some headwinds over alleged contamination and land use since 2006. While te report says the projects remains “blocked”, the companies said La Granja, ranked as the world’s fifth-largest copper deposit, is currently advancing according to plans.

In Arizona, Rio Tinto’s Resolution Copper project has been stalled for more than two decades due to Indigenous and environmental opposition over the sacred Oak Flat site, located on federally owned land.

El Pachón in Argentina, held by Glencore (LON: GLEN), has been delayed by glacier-protection rules and permitting hurdles, though new incentives under President Javier Milei’s RIGI regime may revive development.

GEM’s report does not mention an iconic copper mine that has remained idled since November 2023: First Quantum’s Cobre Panamá. Before Panama’s Supreme Court declared the mine’s operating contract unconstitutional and forced it to shut down, it ranked among the world’s largest copper producers, yielding 350,000 tonnes in 2022, its final full year of operations. The mine contributed about 5% of Panama’s GDP, and First Quantum estimates the suspension has cost the country up to $1.7 billion in lost economic activity.

Perfect storm

Panguna in Papua New Guinea stands as a stark reminder of how ESG concerns, such as water use, biodiversity loss, Indigenous rights, consultation failures and local protests can collide.

Once one of the world’s largest copper-gold mines, the mine operated by Rio Tinto’s unit by Bougainville Copper, closed in 1989 after a violent civil conflict over environmental destruction and inequitable profit sharing. More than three decades later, redevelopment remains uncertain.

While some projects may eventually progress, Faúndez warns that many remain frozen for years, out of sync with surging demand. Rebuilding trust, enforcing higher environmental standards, and stabilizing governance, he said, will be crucial to unlocking the copper needed for the global energy transition.

More News

Gold price extends gain amid US-Iran standoff

Spot gold rose as much as 1.2% to above $5,250 an ounce.

February 27, 2026 | 09:48 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

7 Comments

John Youle

The author is completely misinformed regarding the La Granja project in Peru. Rio Tinto has done a superb job in handling ESG matters from the first day. There has never been a protest, and much less a conflict at the project. I have attended meetings that lasted a whole morning between the CEO and Community Relations Director with local authorities, leaders from the seven communities, Rondero (rural self-defense patrols) leaders, and community members. These meetings were a model of community relations management. La Granja is a 100-year mine with a relatively low grade and complex ore containing significant arsenic and boron. To develop it effectively would require roughly $20 billion or more, with inflation. This is why Rio Tinto sought a partner willing to share the risks and cost (FQML) and why the project is still being explored, rather than developed. The author needs to print a retraction, as his statement is inaccurate and reflects negatively on Rio Tinto and First Quantum.

Cecilia Jamasmie

Thank you for your comment. We have contacted the author of the study cited in this article about your concerns.

Here is what he has to say:

“The study does not dispute that Rio Tinto has made significant ESG efforts at La Granja, especially in recent years. In fact, we acknowledge these improvements directly.

However, our analysis is focused on projects that have faced ESG-related challenges at any point in their development, not just their current status. As documented by sources like the Latin American Conflict Observatory (https://mapa.conflictosmineros.net/ocmal_db-v2/conflicto/view/155), La Granja did experience community opposition, mobilizations, and project delays linked to social and environmental concerns—particularly between 2008 and 2016. These historical issues contributed to delays and investor hesitation, which is relevant to the study’s scope.

Our mention of La Granja is not an indictment of Rio Tinto or First Quantum’s current practices. Rather, it reflects the broader point that ESG challenges—past or present—can have long-term effects on project timelines and investment decisions. Recognizing that does not negate the strong community relations work that may have followed.”

MINING.COM’s own research prior to publication, including interviews, public records, and third-party databases, supports the study’s conclusion that ESG-related factors played a role in delaying La Granja’s development. These factors don’t imply wrongdoing by Rio Tinto or FQM, but are relevant in understanding why the project, despite its scale, remains in pre-development. Some of the sources used were:

https://www.oecd.org/dev/inclusivesocietiesanddevelopment/Peru.pdf

https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/annual-survey-of-mining-companies

https://www.reuters.com/article/peru-mining-idUSL2N17R1DD

https://ejatlas.org/conflict/la-granja-copper-mine-peru

To be clear, the study does not argue that ESG issues are the only reason La Granja remains undeveloped—technical and economic hurdles are clearly part of the picture. But it does conclude that historical ESG challenges had a material impact, and that remains consistent with the record.

Luis Fierro

Its wonderful news ! Perhaps the mining companies will now realize that this is what happens when you privatize the revenues for the benefit of the stockholders, and you offload the costs on the public: privatize the profits and socialize the costs. Negative externalities must be absorbed by those that profit from the economic activity.

Rick Michaels

I am on the periphery here, so forgive my ignorance. What factors qualify a project to be “trapped” by ESG concerns? If a project is feasible but not yet entered permitting, is that considered an “ESG concern”? Seeing 2% for Canada, I am curious to know which projects/deposits are being included in that 2% “on hold”.

Cecilia Jamasmie

A mining project is “ESG-trapped” when it cannot advance due to failing environmental, social, or governance standards.

Common causes include high carbon emissions, biodiversity damage, or water risks.

Community opposition or lack of social license often halts permitting.

Poor governance, corruption, or weak regulation add uncertainty.

Investors and lenders avoid such projects due to reputational and financial risks.

If a project is feasible but not yet entered permitting, is not necessarily affected by ESG issues unless one of more of the criteria listed above applies.

Hope this helps!

Toni Eerola

Yeah, references on the situation may have been good to be added in the text by the author.

Toni Eerola

The problem of those projects is a project location in sensitive contexts prone to conflicts. Of course, mineral deposits are where they have been formed but diverse and divergent human interests may overlap in such areas. A more responsible and careful target selection with avoiding of such contexts may help to avoid conflicts.