Venezuela aluminum restart could cost up to $2.3B: WoodMac

Reviving Venezuela’s idle aluminum industry would require up to $2.3 billion in investment but could help ease a widening supply gap in the Americas, according to a new report from Wood Mackenzie.

The country’s aluminum output has collapsed from peak capacity of more than 600,000 tonnes a year to effectively zero in 2025, removing a once-important source of supply at a time when the US primary aluminum structural deficit exceeded 5 million tonnes last year, the consultancy firm said in its report Beyond oil: What would it take to revive Venezuela’s aluminum industry.

The analysis comes as Venezuela attracts renewed attention following recent shifts in US policy toward the country, raising questions about whether its long-dormant industrial assets could again play a regional role.

Lost capacity

Despite years of underinvestment and outages, Wood Mackenzie said Venezuela retains a rare, vertically integrated aluminum value chain, spanning bauxite mining, alumina refining and primary smelting, historically powered by hydroelectric capacity.

“Unlike some frontier jurisdictions, Venezuela is not starting from zero when it comes to aluminum,” said Uday Patel, principal analyst at Wood Mackenzie. “It already produces, or at least has produced, at an industrial scale.”

Patel noted that the country once ran a sizeable aluminum chain, from alumina refining to metal smelting, while downstream producer Sural previously exported EC wire rod across North America and Europe.

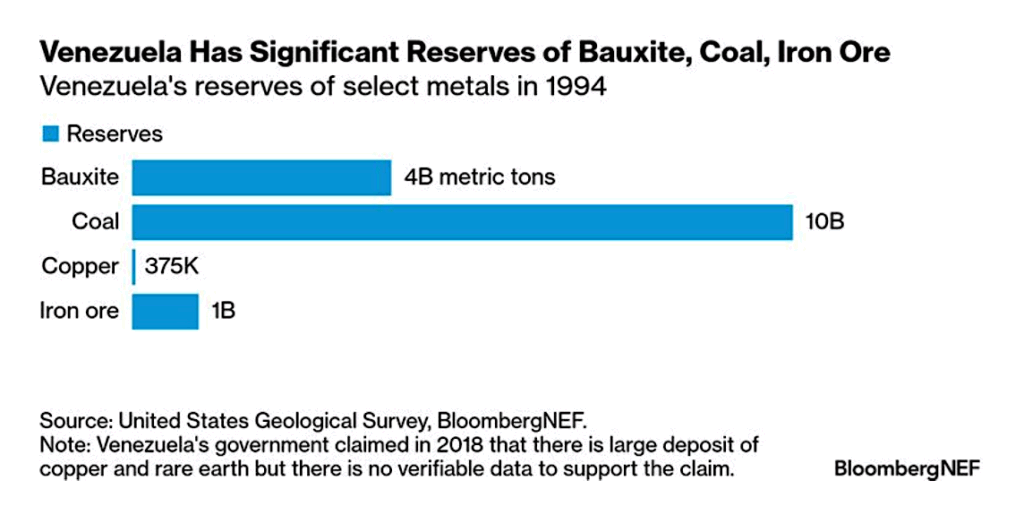

Venezuela also holds world-class bauxite resources, with more than 300 Mt of proved reserves and up to 5,000 Mt inferred, comparable with major global producers.

Broader decline

Not all analysts share Wood Mackenzie’s guarded optimism.

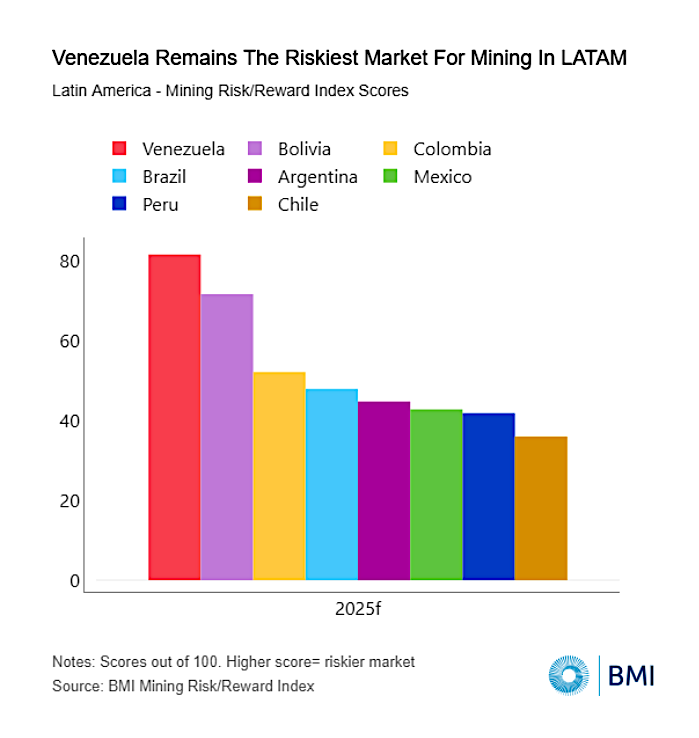

BMI, a unit of Fitch Solutions, sees little reason to expect a meaningful turnaround in Venezuela’s metals and mining sector, even under a post-Maduro government. Over its 2026–2035 forecast period, BMI expects the industry to remain among the smallest and least attractive in Latin America.

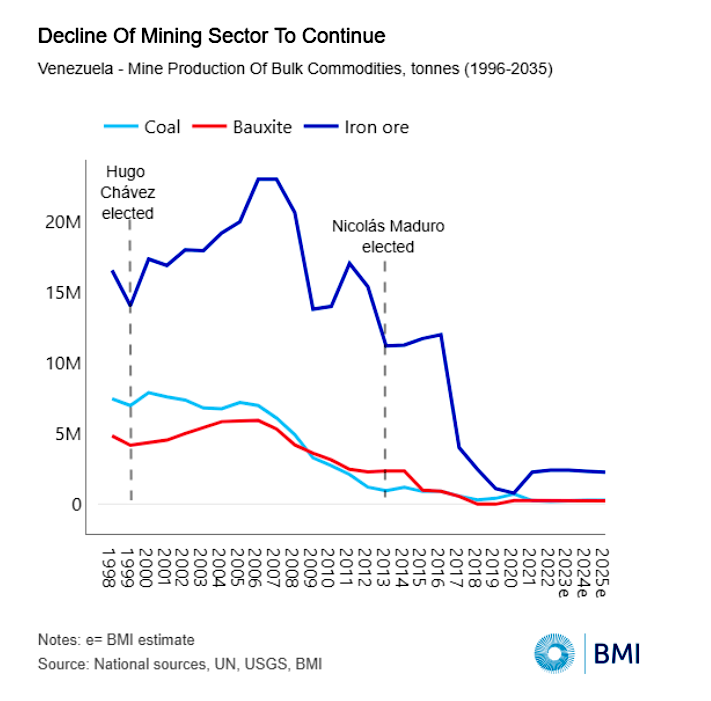

“Like its much larger oil and gas sector, Venezuela’s mining industry has suffered a steep decline over recent decades,” BMI said, pointing to widespread nationalization and chronic underinvestment.

Twenty years ago, the country ranked as the world’s 12th-largest iron ore producer and eighth-largest producer of bauxite. Since then, output has collapsed. Between 2004 and 2024, BMI estimates iron ore production fell from 20 million tonnes to 2 million tonnes, bauxite from 5 million tonnes to 0.3 million tonnes, and coal from about 6 million tonnes to less than 0.5 million tonnes. The consultancy does not expect these trends to reverse, citing degraded infrastructure and years of missed capital spending.

Gold mining is also severely underdeveloped, with operations in Bolívar and Amazonas often controlled by guerrilla groups and criminal gangs, deterring legitimate investment.

Costly hurdles

Against that backdrop, Wood Mackenzie said restoring aluminum capacity would require heavy spending across the entire chain. Reviving the Los Pijiguaos bauxite mine would cost an estimated $100 million to $200 million to repair infrastructure, rebuild processing and haulage systems and reach production of about 2 Mtpa.

Rehabilitating the Interalumina refinery would require a further $500 million to $600 million to restore core processing units and upgrade utilities and environmental controls for capacity of roughly 1 Mtpa.

On the smelting side, Venezuela’s two main plants, Alcasa and Venalum, have been largely idle since a nationwide blackout in 2019. The report concludes that only Venalum is a viable restart candidate, given the condition of Alcasa.

Restarting Venalum would require $1 billion to $1.5 billion to reline cells, rehabilitate power systems and anode production, and address infrastructure and environmental issues, enabling capacity of about 460,000 tpa.

Additional capital would also be needed to secure a reliable electricity supply and overhaul transport infrastructure, both of which have deteriorated significantly.

BMI argues that strategic and critical minerals represent the only plausible long-term opportunity for Venezuela’s mining sector. Government data suggests the Arco Minero del Orinoco hosts copper, nickel, coltan, titanium and tungsten, all minerals deemed critical to US national security.

“Given the opaque nature of Venezuela’s official and black-market economy, we cannot say for sure what the real prospects are for critical mineral development,” Michael Cembalest, chairman of market and investment strategy for J.P. Morgan Asset & Wealth Management, said in a note this week.

“But it’s notable that China, which controls the vast majority of critical mineral mining and processing activities around the world, is active in Venezuela.”

New code required

BloombergNEF echoes this scepticism, noting that metal production has declined by more than 90% over the past two decades. According to BNEF, reviving the sector would require a new transparent mining code, improved security and rule of law, major investment in infrastructure and at least a decade of sustained reform.

“The US government’s intervention has put Venezuela’s resources in the spotlight,” Sung Choi, BNEF’s specialist in metals and mining, said. “But the country is crippled by poor geological data, low-skilled labour, organized crime, lack of investment and a volatile policy environment.”

Constraints for Venezuela’s mining sector today are not geological, Natixis analysts led by Benito Berber said in a separate research note last week. “They are political risk, sanctions exposure, insecurity in mining regions, weak rule of law, and the absence of enforceable contracts. Until those fundamentals change, serious Western capital will likely remain on the sidelines.”

Ironically, Venezuela’s vast oil reserves may be the biggest barrier to mining investment. Oil projects are faster and cheaper to develop than mines, making them a higher priority for both companies and governments.

As a result, experts say Venezuela is unlikely to become a meaningful player in global critical minerals markets anytime soon. A Washington-friendly government could pursue a Ukraine-style minerals agreement with the US, but BMI cautions that reliable geological data are virtually non-existent. Extensive exploration would be required before miners could commit capital, and Venezuela’s high-risk profile means only exceptional deposits would attract investment.

Even within aluminum, Wood Mackenzie said investors would face persistent structural risks, including chronic power instability linked to the Guri hydroelectric complex, security concerns and aging equipment. Patel said any serious restart effort would require strong investment protections, potentially including tariff-free access to the US market, to offset the high-risk operating environment.

“While reviving Venezuela’s aluminum sector presents significant opportunities, it also comes with major challenges,” Patel said. “In the end, it will come down to a trade-off between political and strategic expediency and economics. If conditions are met, it could take only two to three years to fully reestablish the aluminum value chain.”

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments