Anglo-Teck deal hinges on troubled copper mine in Chile

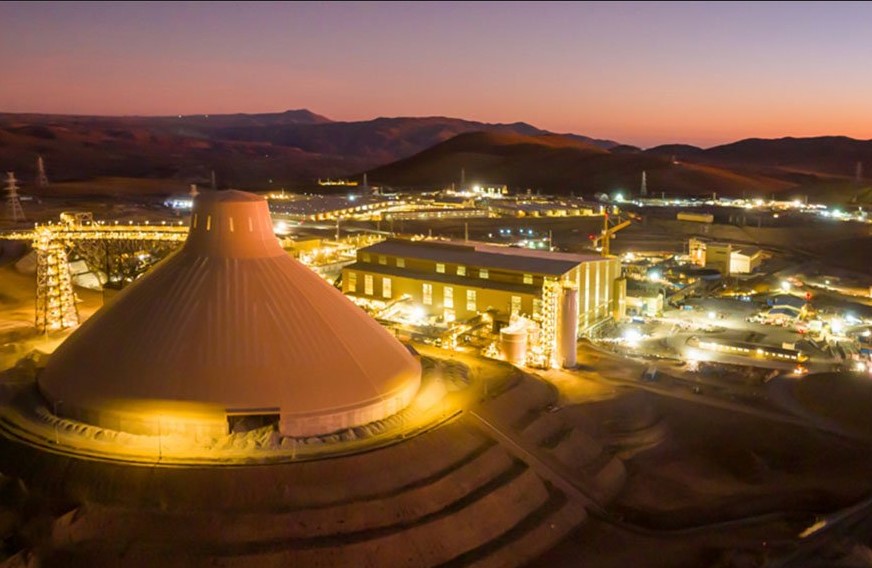

At the heart of one of the mining industry’s most ambitious combinations is a plan to fix a problematic Teck Resources Ltd. copper mine high in Chile’s Atacama desert, and ultimately to integrate it with a vast neighboring operation that has long been a jewel in Anglo American Plc’s crown.

That, however, will require resolving complex operational troubles that have plagued Quebrada Blanca, known as QB — and then navigating relationships with partners in Collahuasi, a mine Anglo doesn’t control.

Teck has staked its growth plans on QB, but a major overhaul of the mine was a headache from its early days, coming in more than 80% over budget and years behind schedule. While delays and overruns are not unheard of in the industry, the operation has also since struggled with instability in the pit and plant, a ship-loader outage and now waste storage.

The travails forced Teck to trim output guidance in July, and earlier this month — just days before announcing a more than $50 billion merger agreement with Anglo — it said it would defer decisions on growth projects to focus on fixing QB.

“Quebrada Blanca has sizable technical challenges to reach capacity,” said Juan Ignacio Guzman, who heads GEM, a mineral consulting firm in Chile. “The synergies it could have with Collahuasi aren’t simple.”

Still, the benefits of a working combination would be hefty, in an industry where vast, usually distant, operations mean substantial synergies are hard to come by. Tying up with Collahuasi, specifically processing its richer ore at QB plants, could mean an average annual boost to Ebitda of $1.4 billion, the two companies said. The revenue synergies would come on top of the $800 million a year in cost savings from more standard areas like procurement and corporate functions in a combined company.

“I think it’s conservative,” said George Cheveley, portfolio manager at Ninety One, referring to the $1.4 billion boost. “The optionality to expand and develop that complex over multiple decades is not in that number.”

Under plans sketched out by the two companies this week, a roughly 15-kilometer (9.3-mile) conveyor would be built to feed Collahuasi’s high-quality ore into QB’s new processing plants. That would generate the equivalent of a new mine’s worth of supply — an incremental annual output of about 175,000 tons of copper from 2030 to 2049 — at a fraction of the time and per-ton cost.

One scenario could see combined annual output approach 1 million tons by the early 2030s, according to industry consultancy CRU Group. That could put it above BHP Group’s Escondida, though not necessarily for the long-haul, as the world’s largest copper mine.

“It is absolutely feasible that a Collahuasi-QB complex could surpass Escondida’s level of copper out-turn in the early 2030s,” said CRU analyst William Tankard.

It’s the kind of cost-saving arrangement the industry has been touting for decades, where neighboring mines gain outsized benefits with relatively small investments, helping to boost global production of a metal vital for the energy transition.

But these deals are slow and challenging. Chilean state-owned giant Codelco and Anglo have held discussions for years over ways to integrate their Los Bronces and Andina mines, and are yet to finalize an arrangement.

Collahuasi and QB have more complicated ownership structures. Collahuasi — jointly owned by Anglo and Glencore Plc, with 44% each, plus a Mitsui & Co.-led consortium holding 12% — is independently managed. At QB, Teck does own the majority share, but still has Japan’s Sumitomo Metal Mining Co. together with Sumitomo Corp. as a 30% partner, and Codelco with a 10% stake.

“Among the challenges will be governance, due to the multiplicity of partners,” said Juan Carlos Guajardo, founder of consultancy Plusmining.

Then there’s the scale of the problems at QB. To grapple with these before committing, Anglo sent technical experts to QB and sat with independent engineers, Anglo chief executive officer Duncan Wanblad told analysts this week.

The troubles are such that some Teck shareholders worry Anglo may be getting a steal by swooping in at a low point — but Anglo’s investors fear it may be getting more than bargained for.

“It’s beyond me why Teck would surrender control of one of the world’s great copper-rich mining companies for nil premium, especially when they’ve inexplicably chosen to price the deal after underperforming Anglo by so much,” said Tim Elliott, head of mining at Regal Funds Management. “Teck should fix their key asset first, then test the market properly from a position of strength.”

Unions at the site say teams have been filling cracks around the tailings dam embankment, while waste is piling up because of the filtering issues and there’s also been pipe corrosion. The slower-than-expected ramp-up, meanwhile, is squeezing production bonuses for workers.

“This hits the wallet,” said David Munoz, an official at one of the main unions at the mine. “We don’t do less work than at other mines but we get less because of these issues.”

QB uses the so-called centerline cycloned sand dam method, which splits coarse material from fines, with the sand used to raise the embankment. The slower-than-expected drainage creates a bottleneck for production.

Earlier this month, Teck stepped up efforts to resolve the tailings issues, bringing in a former senior BHP executive as special adviser. Work is focusing on mechanically raising the dam wall and improving drainage times, the company said in an emailed response, adding that dam and pipe maintenance is normal and doesn’t pose any risk.

The ramp-up troubles are not dissimilar to Anglo’s own at Quellaveco in Peru, Wanblad said, a reminder of the copper industry’s struggles to expand supply just as the world demands more of the red metal. Quellaveco uses a similar tailings system.

“The reality is that these major operations do just sometimes take time,” he said.

(By James Attwood)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments