Column: A quiet revolution is unfolding in the mining sector

The world is going to need a lot of copper and other critical metals if it is going to pivot away from fossil fuels. But can the mining industry deliver?

The challenges are huge. Ore grades at existing copper mines are steadily falling, big new discoveries are becoming rarer and development times can stretch up to a decade.

Part of the solution is to increase the efficiency of the mining process, which has historically been both highly polluting and wasteful.

Back to the future

The world dug up 650 million metric tons of copper between 1910 and 2010 but 100 million tons never made it to market, according to a 2020 research paper by Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute.

All that metal is still there lying in tailings ponds, a potentially massive resource awaiting the right technology to unlock it.

Rio Tinto has already successfully separated critical metals such as scandium and tellurium from waste streams at existing operations.

Others are now looking at ways to extract value from the vast legacy of past mining activity.

Hudbay Minerals, for example, is evaluating the potential for re-mining tailings at the Flin Flon site in Canada’s Manitoba. The mine closed in 2022, leaving nearly a century’s worth of minerals-rich waste.

Australia’s Cobalt Blue Holdings, which has been collaborating on the Flin Flon project, has also signed an agreement with the Mount Isa city council in Queensland to explore re-working pyrite tailings as a potential alternative source of sulphur once the town’s copper smelter closes.

These and many similar projects are still only at conceptual or pilot stage but India’s Hindustan Zinc is scaling up with a $438 million commitment to process 10 million tons per year of tailings at its Rampura Agucha mine, the world’s largest zinc mine.

Less waste

While miners are collectively reassessing the value of legacy waste, they are also working out how to produce less waste in the first place.

This comes with both economic and environmental upside. The mining industry currently generates over seven billion tons of tailings per year and the amount is rising as ore grades fall.

Much of the work in this area is incremental in nature. Glencore Technology, for example, has been steadily improving its ISAMill grinder to handle increasingly coarser particle sizes. The aim is to reduce the amount of ore grinding to save water and reduce tailings waste.

The company’s Albion Process for leaching can lift copper recovery rates to over 99% and reduce operating costs by up to a third, allowing development of complex ore-bodies that wouldn’t be viable with traditional technologies.

Others such as Allonnia, which describes itself as a bio-ingenuity company, are pioneering more revolutionary approaches.

The company’s D-Solve technology uses microbes to selectively extract impurities such as magnesium from concentrates.

Allonnia has just partnered with the Eagle nickel mine in the United States for an onsite unit to pilot technology that in laboratory tests can improve nickel grades by 18% and cut magnesium impurities by 40%.

Big tech meets old tech

The new overarching technology that can bind all these innovations together is artificial intelligence (AI).

Majors such as Rio Tinto and BHP are already using AI in autonomous haulage systems and to predict maintenance downtime rather than reacting to equipment failures.

Generative AI is the next big leap forward. BHP uses it in combination with “digital twin” technology, a real-time virtual replica of the mining process, at its South Australian copper mine and the giant Escondida mine in Chile.

GenAI models at Escondida “inform ore blasting and blending strategies, identify mine areas with challenging ore characteristics, and support the implementation of SAG mill model predictive control,” according to BHP.

US copper producer Freeport-McMoRan has partnered with consultancy group McKinsey to use AI to boost production at its North American operations, which were facing declining output due to mature mines and aging process technology.

Integrating traditional mining with data engineering allows for real-time adjustments to processing rates to handle variable ores. When AI was trialled at the Baghdad mine in Arizona, it led to a 5%-10% increase in copper production.

Rolling it out across the company’s other American operations is projected to lift output by 90,000 tons each year.

That’s equivalent to a new processing plant, which would come at a cost of over $1.5 billion and a timeline of eight to ten years for planning, construction and commissioning.

Future mining

Mining, it is often said, is a dirty business.

The proof lies in the billions of tons of sludge sitting in tailings ponds around the world. The consequence is public antipathy to new mine projects, which is one of the reasons it takes so long to build and commission a new one.

Mining has also been a highly inefficient business in the past. Too much mineral value has been either discarded as waste or simply left in the ground because the technology didn’t exist to treat such low-grade ore.

That’s changing as one of the world’s oldest industries rapidly modernizes, combining innovations in traditional processing with new technologies such as bio-engineering and AI.

This is a quiet revolution playing out in multiple laboratories, pilot plants and data centres around the world.

But the promise is one of a much cleaner and more efficient sector, which may just mean the world isn’t going to run out of copper after all.

(The opinions expressed here are those of the author, Andy Home, a columnist for Reuters.)

(Editing by Elaine Hardcastle)

More News

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

9 Comments

Craig

No one argues that mining’s legacy has left billions of tonnes of tailings at mine sites around the world. Metallurgical recovery of metals has improved over time, implying that old tailings are a vast source of mined metals. However, few journal articles actually cite the metal grades or expected recoveries of metals from reprocessing old tailings. Technical journals should dig deeper and report grade and expected metal recoveries for these purported, vast resources of metals in mined materials. Enough of the arm waving !

Bigblaz

I agree. Also there will be a tailings outcome, with reduced metal content that may be attractive to scavenge in the future.

I would look at lead tailings as it is often overground in the milling process due to it’s density that leads it to report às oversize in eg cyclone classifiers. This makes its recovery by froth flotation less efficient.

Jim Sheil

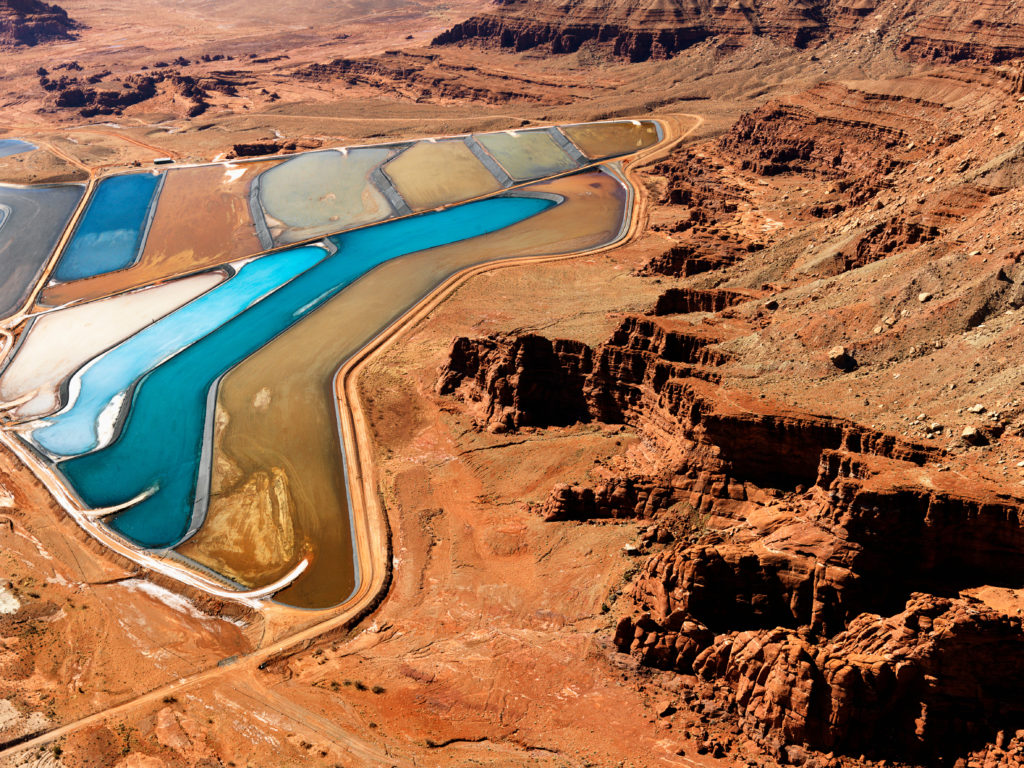

The title photo is of evaporation ponds at Intrepid Potash’s Moab solar-solution mine, not tailings pods.

Amanda Stutt

Hi Jim, this photo is licensed from our Adobe stock account.

Paul Kleimeer

Like the setup you see when fueling stations are shutter because of mass leakage these plastic pipe setups are the viable part but the same solution or acid leaching could be carried out at just every mineral site in this planet as part of the drinking wat3 supply source mineral extraction as the byproduct sources from millions of sites could collectively provide all of our mineral requirements and do it with minimal labour costs as these leachate extraction processes are basically a pumping filtration process water mineral and geothermal sourcing roled into a multi operational self standing extraction resource when all of these technologies are parked together viable unit processing encourages nonviable such as geothermal developement roadblocks can be surmounted .One of the major road blocks to these efforts are unconfined leachate extraction with bioengineering and even pressure create isolation cane make this revolution acceptable let’s op

Michael James Bue

There are gold-silver tailings in the Philippines from former mining operations that grade up to 3g/t AuEq. The gross value is over $300/t at today’s Au price. The economics for a gravity separation plant without adding chemicals are fantastic. The issue is that most the former illegal mining operations used mercury to recover about 50% of the Au and sometime cyanide leach. The ore and waste products of a gravity plant will contain the original Hg and cyanide, so separate operations are required to boil off and recover the Hg. Proper storage of the new tailings is critical. Overall, the cash operating cost will be about $1,500/oz allowing a very healthy profit margin combined with cleaner tailings.

martin nelson

There can be possible economic mineralization in waste dumps, tailings, and low grade stockpiles. There can also be possible economic mineralization in waste and low grade that has been backfilled underground. Huge quantities of tailings have gone into underground backfill.

It all depends on the economics [location, grade & metallurgy] – is there any profit to be made??

ore=mineralized rock that can be mined/processed at a profit……

George Seoloane

Please send me more information regarding tailing

Albert Reinhardt

Hi, please keep me updated on new developments in Tailings resource recovery technology news resource demand in the west and investment finance news.