Global inflation ends era of ever-cheaper clean energy

The era of ever-cheaper clean power is over, giving a fresh jolt of uncertainty to global energy markets battered by one supply crisis after another.

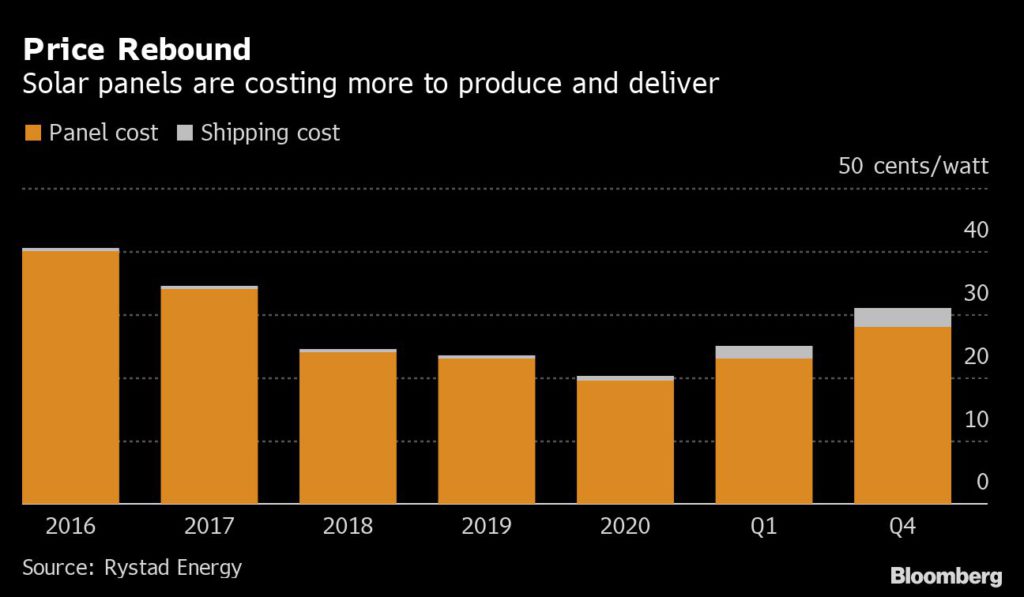

Relentless price declines over the past decade made renewables the cheapest sources of electricity in much of the world. In the past year, though, prices for solar panels have surged more than 50%. Wind turbines are up 13%, and battery prices are rising for the first time ever.

As pandemic-induced supply delays ensnare everything from cars to salads, green energy’s price hikes may not come as a surprise. But shipping backlogs and commodities shortages are coming at a particularly vulnerable moment for wind and solar. After years of rapid-fire advances in technology and manufacturing, there are fewer opportunities left to cut costs without sacrificing profits. Instead of perpetually falling, prices will now ebb and flow based on the cost of raw materials and other market forces.

For energy markets grappling with blackouts and extreme price volatility in the green transition, clean-power inflation is another wild card. Policy makers, accused of adding wind and solar so rapidly that electric grids have become unstable, are under pressure to ensure the entire system is more reliable — by pairing solar with batteries, for example, or keeping aging nuclear plants running for longer.

“From now on, what’s going to make the difference around the expansion of solar and wind is not going to be costs — how low can you go? — but value,” said Edurne Zoco, executive director of clean technology and renewables at research firm IHS Markit Ltd.

Higher interest rates are also threatening to increase costs for wind and solar projects as central banks weigh tighter monetary policy to curb inflation, said Julien Dumoulin-Smith, an analyst with Bank of America Corp.

“One of the single most important inputs that go into these highly levered projects are rates,” he said. “Interest rates have only gone down for a straight decade.”

Climate hawks need not fear renewable-energy inflation, however. Even with the recent rise in costs, wind and solar have evolved from expensive, niche sources of electricity to become competitive with fossil fuels. Renewables remain cheaper on a relative basis than fossil fuels in much of the world, and prices for oil and natural gas have surged over the past year. Over the long term, prices for wind and solar will continue to decline, albeit at a slower pace. That means clean-energy installations are expected to keep growing rapidly in the coming years.

Still, the industry is wrestling with the immediate effects of supply-chain snarls. Burlington, Vermont-based solar developer Encore Renewable Energy LLC is paying about 35 cents a watt for panels, up from 30 cents in mid-2020, according to Chief Executive Officer Chad Farrell.

Raw materials now account for 70% of the cost of finished modules, leaving suppliers with almost no room to trim expenses, said David Dixon, a senior analyst with research firm Rystad Energy. A shortage of polysilicon, one of the key materials for the photovoltaic cells that make up solar panels, increased expenses last year, and shipping costs also rose.

Invenergy, a U.S. developer of wind and solar projects, has been forced to delay some projects because it can’t get panels, said Art Fletcher, the company’s executive vice president of construction. Though shipping expenses are beginning to decline after jumping last year, the renewables industry as a whole is undergoing a transformation, he said.

“I don’t believe we’re ever going back to where we were two years ago,” Fletcher said.

Canadian Solar Inc., one of the world’s largest panel makers, said it no longer makes sense for the industry to constantly slash prices. “There will be an end for this price drop,” the company’s chairman, Shawn Qu, told a virtual BloombergNEF event on Nov. 30. “There’s a cost for going green and carbon neutrality.”

The Solar Energy Industries Association and Wood Mackenzie Ltd. forecast last month that U.S. installations will drop 15% in 2022, about 25% below the trade group’s September forecast.

Supply-chain kinks may ease this year as China spends billions on new factories to produce polysilicon. That may cut prices in the short term, but it’s less likely to lead to sustained reductions.

“We’re getting to the tail end of price declines,” said Dixon. “Commodity prices will be the sole determinant of module prices.”

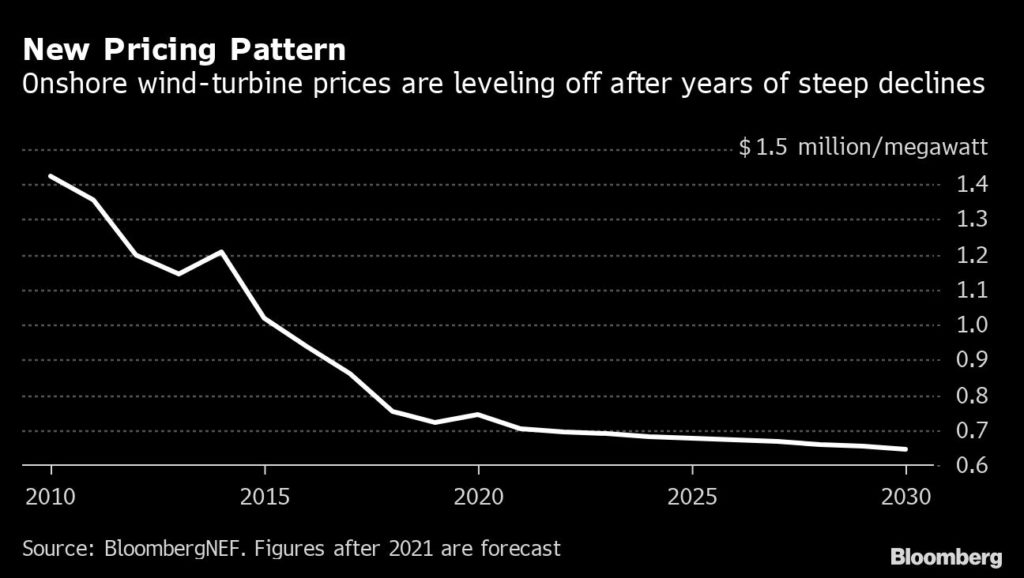

The wind industry is going through a similar transition. Prices plunged 48% in the decade through 2020, but are now leveling off and are expected to slide 14% through 2030, according to BloombergNEF.

“That’s a sign of the industry maturing,” said BNEF wind analyst Oliver Metcalfe.

Manufacturers will continue to reduce per-megawatt costs with larger installations. However, these massive turbines — almost as tall as the Eiffel Tower — require more materials, especially steel, which surged in 2021 and will likely remain costly for the next several years. Supply-chain issues boosted prices for onshore wind turbines 9% in the second half of 2021.

In some regions, developers have already installed turbines in the best locations and now are looking at less breezy areas or smaller sites. That means they may be using turbines designed for slower windspeeds or placing smaller orders, both of which lead to higher per-megawatt prices.

The world’s largest wind turbine maker, Denmark’s Vestas Wind Systems A/S, had to cut its profit forecast last year as it faced rising costs from key commodities and persistent supply-chain disruptions. Something will need to change for the industry to be able to deliver enough wind power capacity to hit the world’s climate goals, the company said.

“We have to put up a warning flag here,” said Morten Dyrholm, senior vice president at Vestas. “We need to focus on profitability across the sector.”

Battery costs

Batteries have also been hit by inflation. BNEF said late last year that it expected prices for battery packs to climb this year for the first time in data going back to 2010. The 2.3% increase can be blamed on soaring prices for the metals batteries contain, booming demand worldwide and strained supply chains.

But compared with wind and solar, batteries are a much newer part of the clean-energy landscape. Suppliers are still experimenting with new chemistries and ramping up production capacity, which means there’s still room for more significant price cuts.

Fluence Energy Inc., a grid-scale storage developer, has seen delays and increased costs to ship batteries from its contract manufacturing facility in Vietnam, but the company doesn’t expect that to last.

“This backlog that has been created is really being worked through,” said Chief Financial Officer Dennis Fehr.

While some of the supply-chain issues bedeviling renewables developers are easing, George Bilicic, head of global power, energy and infrastructure for Lazard Ltd., said the industry is undergoing permanent changes. Without any new technological breakthroughs or major consolidation, prices are stabilizing.

“The story about big cost declines is that large cost declines won’t be the story anymore,” Bilicic said.

(By Will Wade, David R Baker and Josh Saul, with assistance from David Stringer and Will Mathis)

More News

Contract worker dies at Rio Tinto mine in Guinea

Last August, a contract worker died in an incident at the same mine.

February 15, 2026 | 09:20 am

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments