Rio Tinto adds aluminum markups as Trump tariffs drive up consumer costs

Rio Tinto Group is imposing surcharges on aluminum shipments it sells to the US, a move that threatens to further disrupt a North American market already roiled by import tariffs that are driving up costs for consumers.

The Anglo-Australian mining giant is including the extra charge on aluminum orders delivered to the US citing low inventories, as demand starts to outstrip available supply, according to people with direct knowledge of the matter.

The US relies heavily on foreign aluminum supplies as it doesn’t have the capacity to produce enough to meet demand. Canada is its No. 1 foreign supplier, accounting for more than 50% of US imports.

The surcharge adds stress to an already extremely constrained US market after President Donald Trump earlier this year imposed a 50% import tariff on the lightweight metal, which is used in everything from soda cans to construction. Tariffs made Canadian shipments too expensive for American metal fabricators and consumers. Instead they’ve drawn on domestic stockpiles and exchange warehouses, leading supplies to dwindle and prices to jump.

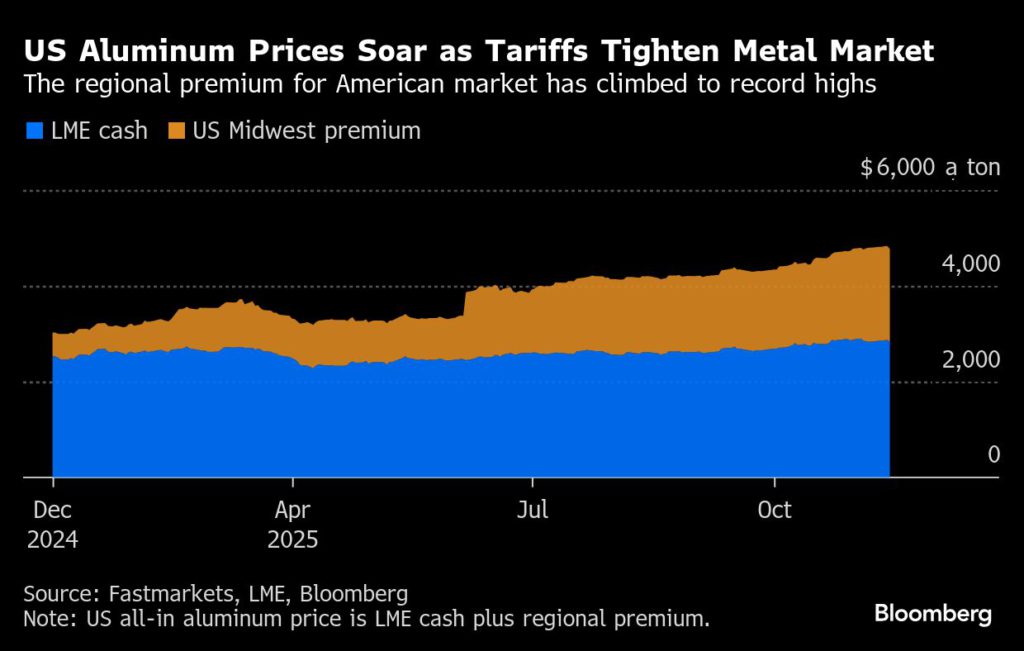

The latest markup amounts to a charge on top of a charge, since US aluminum prices already include the so-called Midwest premium — an added cost above the London benchmark price that reflects transportation, storage, insurance and financing — to deliver the metal into the American marketplace. Each global region has its own premium, which is usually set by pricing reporting agencies.

The new surcharge ranges from one to three cents above the Midwest premium, said the people familiar, who asked to not be identified discussing private contract details. Though that’s a modest amount, the markups plus the Midwest premium translate into an extra $2,006 per ton on top of the raw metal price of about $2,830, implying a more than 70% premium. That’s above Trump’s 50% import duty.

Consumers and traders describe a market that’s all but broken, with the surcharge the clearest sign yet of how deeply its structure has been disrupted by Trump’s levies. The price for aluminum delivered to the US, including the benchmark price and the Midwest premium, reached a record high last week as stockpiles shrink.

It’s “a new reality now that if the US wants to attract aluminum units, it has to pay up because the US is not the only market that actually is short,” said Michael Widmer, head of metals research at Bank of America Corp.

Rio Tinto declined to comment. The head of the Aluminium Association of Canada, Jean Simard, explained that buyers asking for payment terms on contracts beyond 30 days should expect a premium to offset higher costs of financing for producers.

“The 50% tariff on aluminum put in place by the US administration significantly increased the risk of holding aluminum inventory in the US as any tariff change could directly impact the economics of cash-and-carry inventory financing trades,” Simard said.

In Europe, which is also a net importer of aluminum, the regional premium has dropped about 5% from a year ago. But it has been recovering in recent weeks amid supply outages and the implementation next year of a European Union fee on imports based on greenhouse gases emitted during their production, according to Morgan Stanley analysts including Amy Gower. The analysts expect the current global backdrop to take the global benchmark above $3,000 a metric ton.

Trump set aluminum tariffs at 25% in February and doubled the rate in June in what he said is an effort to protect American industry. US importers turned to domestic supplies to try and evade paying the steep import tax.

US warehouses used by the London Metal Exchange, the biggest global market for metals trading, don’t have any aluminum left after the last 125 tons were withdrawn in October. Exchange inventory typically serves as the last resort for physical supply. Top US aluminum producer Alcoa said during its third-quarter earnings call that domestic stockpiles stood at only 35 days of consumption, a level that typically triggers higher pricing.

Before the recent price increase, aluminum producers in Quebec had been sending more of the metal to Europe to compensate for the loss-making US market. Quebec represents about 90% of Canada’s aluminum-making capacity, with the US as the province’s natural buyer given the close proximity.

The tightness in the US market has been exacerbated by language in the presidential proclamations that says aluminum tariffs won’t apply to imported products if the metal was smelted and cast in the US. That’s created more demand for US-made aluminum from overseas manufacturers, who use it to make products that are then shipped to the US duty-free.

“If you are a net importer of aluminum units, and you’re putting a tariff on those imports, ultimately, it’s not the supplier who pays — it’s the consumers, hands down,” said Bank of America’s Widmer.

(By Yvonne Yue Li)

{{ commodity.name }}

{{ post.title }}

{{ post.date }}

Comments