Much like the reference in this piece’s headline, it’s a cliché to call a country the Saudia Arabia of something.

The top search suggestion at the moment is the Saudi Arabia of wind. That’s Boris Johnson’s dream for the UK and from a leader with an affinity for hot air, perhaps not unexpected.

The Saudi Arabia of lithium query takes you to a story about Chile, which is wrong. Neither is it Afghanistan as this article in the NYT would have it. It’s Nevada; Elon Musk confirmed it last year.

The Saudi Arabia of sashimi is… well just google it. (it’s Palau – ed.)

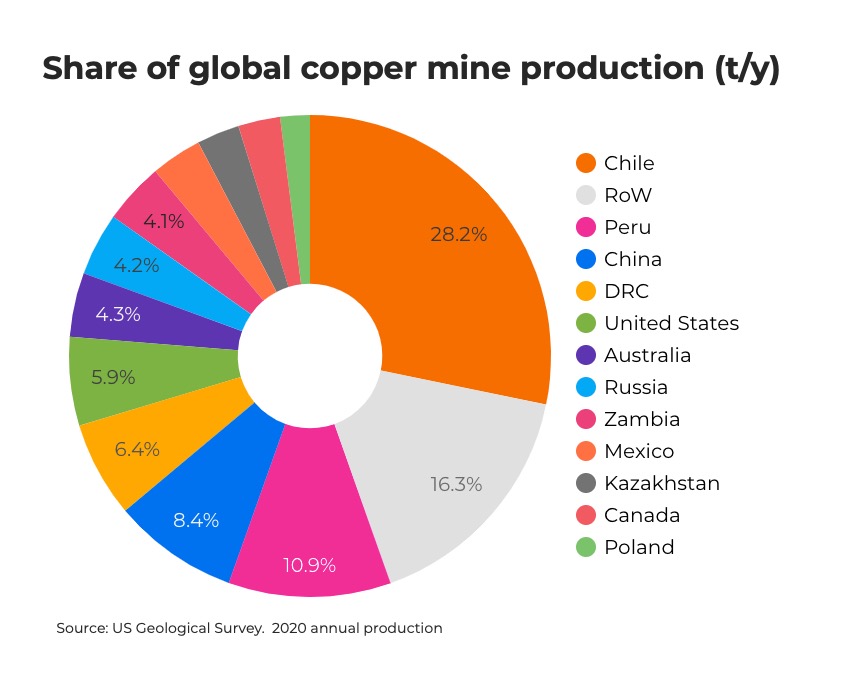

Chile is not the Saudi Arabia of copper either.

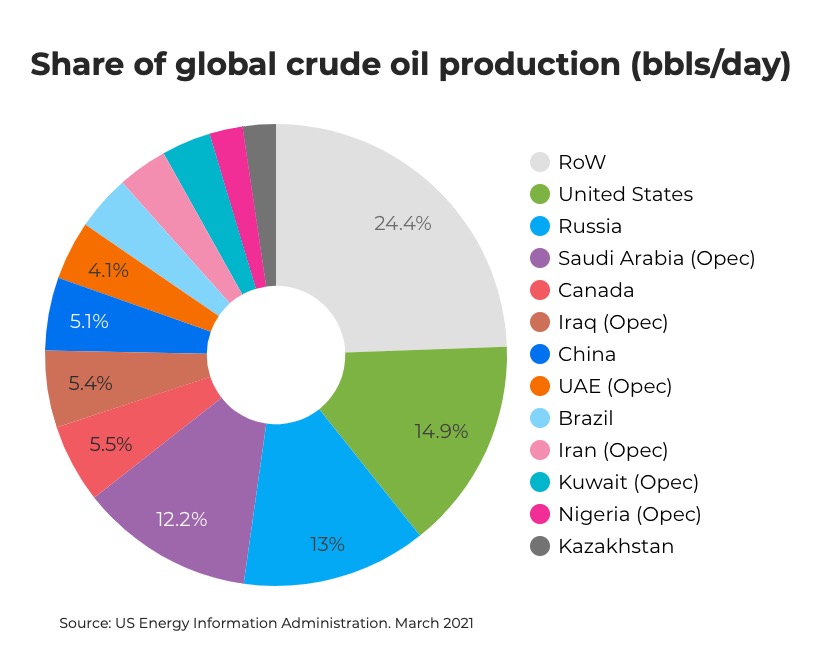

It’s the Saudi Arabia, Iraq, UAE, Iran, Kuwait, Nigeria, Angola, Algeria, Venezuela, Libya, Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea of copper.

Chile’s share of global copper output is on par with the combined output of the 13 members of Opec in the crude trade.

In 2020 the South American nation produced 5.7m tonnes of copper out of a global total of 20.2m tonnes, according to the US Geological Survey. Opec countries were responsible for 24.3m of the 76.1 million barrels per day produced during March this year, according to the US Energy Information Administration.

Chile and Peru together constitute close to 40% of world production, which is roughly the share of what is known as Opec+ (add Russia). And consider that Chile and especially Peru suffered frequent covid-related mining disruptions last year (not to mention blockades at some of the biggest mines and transport strikes).

The concentration at the top is only going to increase. The Democratic Republic of the Congo could as soon as next year overtake China as the no 3 producer when the Ivanhoe-Zijin JV, Kamoa-Kakula, adds 400,000ktpa to the country’s total (and doubling its contribution six years later).

Apart from Rio Tinto’s much-anticipated block cave at Oyu Tolgoi (330ktpa) in Mongolia on the Chinese border, the only near-production projects close to this size are in South America.

Anglo American’s greenfield Quellaveco project (300ktpa) in Peru and Teck Resources’ phase 2 at Quebrada Blanca (295ktpa) in northern Chile will further entrench the two countries’ dominance.

As in other spheres, China plays the long game in mining.

It bagged the largest new copper mine to come on stream in decades – Las Bambas in Peru – by making its sale to a Chinese concern a requirement for approving the 2014 Glencore-Xstrata merger.

In 2016, China Moly picked up Tenke Fungurume in the biggest overseas splash since Las Bambas, paying $2.7 billion to take it off Freeport-McMoRan and Lundin’s hands.

In all, China has spent $16 billion on buying copper projects around the world and at the moment owns 30 operating copper mines and 38 exploration projects.

That’s over and above Beijing’s annual foreign direct investment in mining and exploration, which reached $2.2 billion in 2019.

It’s not only primary production that’s highly concentrated, there’s a lock on the midstream.

Overall, 63% of China’s copper concentrate comes from Chile and Peru, and after decades of investment in the sector, the country refines over 40% of the world’s copper, six times its nearest rival, Japan.

The Tenke deal supercharged the 4C supply chain – Congo-Copper-Cobalt-China – as Chinese imports of concentrate from central Africa and elsewhere accelerated towards 2020’s total of just under 22m tonnes per year.

The Biden administration reportedly wants to copy the Chinese playbook, but in order to placate environmentalists will skip the mining part

Cobalt is a by-product of copper mining — primarily in the DRC which is responsible for some two-thirds of global output. China owns 82% of global midstream processing of cobalt for batteries. For nickel in the EV supply chain it’s 65%.

The Biden administration reportedly wants to copy the Chinese playbook, but in order to placate environmentalists will skip the mining part.

In the words of one official involved in critical minerals policy, “it’s not that hard to dig a hole. What’s hard is getting that stuff out and getting it to processing facilities.”

Just like all the oil processing facilities in the US shielded it from the Opec-induced oil supply shocks of the 1970s. Right?

While the Middle-East is a volatile region (to use a well-worn euphemism), its hereditary leaders and pseudo-democracies have a way of keeping the oil flowing regardless of any palace intrigue, proxy wars, or sanctions.

In contrast, Chile and Peru are in the early stage of fundamental political shifts driven by elections fought over income inequality, poverty and the environment – hardly on the political agenda in places like Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states.

A debate between Opec’s crown princes and emirs has sent oil to three-year highs, up 50% in 2021.

Let’s count the ways Chile can cause a copper market meltup:

It’s rewriting its Pinochet-era constitution, new copper windfall taxes and royalties already approved by the lower house, could, to put it mildly, dampen enthusiasm (your last euphemism – ed.) for new projects, so-called tax stability deals for half the country’s mines (including Escondida, the copper world’s Ghawar) expire in 2023 if they last that long, a powerful mining union is lobbying for state-owned Codelco to have dibs on projects, and if the current frontrunner becomes president in November elections he would be the first person from the Communist Party to do so.

Daniel Jadue also has other ideas to increase the state’s take and involvement – creating a Codelco for lithium (gentle reminder: Codelco was created by seizing mines from US companies in the 1970s) and like Indonesia renegotiate state shareholding in private companies like Freeport had to with Grasberg.

Another successful Indonesian strategy Chile and others would want to copy is to force miners to build smelters and refineries in-country by banning ore exports.

A bit like the current US administration’s clever strategy around critical minerals, focusing on processing facilities, except Chile also produces feedstock for said facilities.

Now take all of the Chilean political and mining trends, turn them up a few notches, and apply to Peru and its new president Pedro Castillo.

At the start of his campaign, Castillo said he wanted to nationalize the mines but later softened his stance by calling for Chile-like royalties in the 70-percents.

This is a recent headline about Castillo’s latest plans for the industry:

Peru’s Castillo expects mining firms to accept “prudent” tax changes, adviser says

You can read that as having a conciliatory tone, or perhaps it sounds more like: “Nice little copper mine you have there. It would be a shame if something were to happen to it. We’ll make you an offer you can’t refuse.”

The copper-oil analogy only goes so far.

While regional co-operation to align mining rules for Chile, Peru, Argentina, Bolivia and others so as to “not compete for investments” (Jadue again) is being discussed, an Opec-like cartel in copper is never going to happen.

Most Opec disagreements are about how much to up production (the UAE wants to pump more oil now because the assumption is as the world moves away from fossil fuels it would be stuck with stranded oil and gas assets down the line).

Codelco is spending more than $40 billion just to keep output steady. Opec-members output hikes can also hit oil markets within months. For copper it takes years, often decades to bring new supply online.

Low and declining grades and with it ever costlier and bigger mines, uninspiring green discoveries, modest brownfield expansions, thin project pipelines, underinvestment in exploration, and glacially slow permitting processes, have become rules of thumb in the industry. And when tailings reprocessing is being discussed as a significant source of new supply, you know something in the industry has changed.

Depletion is oddly little discussed (must be in miners’ DNA – it’s always about the next discovery, not this old hole in the ground – ed). A recent study found that most porphyries (which supply 80% of the world’s copper) are fast nearing the end of their productive life due to the specific nature of how these deposits are formed.

The copper price is down 10% since hitting all-time highs of $10,500 a tonne ($4.75/lbs) in May and forecasts are for further declines.

Two years out among more than 30 investment banks, economists and research houses polled consensus is for an average $8,131 a tonne ($3.68/lb).

Technically, that means copper is entering a bear market.

But it’s worth remembering that the metal also traded at these levels as far back as 2011.

Rapid demand growth and rising risks to supply since then does not seem baked into today’s price, much less in continuing declines.

2 Comments

Herman Grutter

Say again Frik: So why is the price falling ?

Frik Els

Hi Herman, bears point to China: it’s a price sensitive market (Shanghai still >$10k), substitution, pandemic stimulus effects fading, Beijing removed all subsidies for new solar, wind projects. Also healthy skepticism about US green energy, infrastructure build-out being another false dawn. Next 3–5 years there will be substantial tonnes coming online – Grasberg underground (400k), Kamoa, Quellaveco, QB2, Qulong (Tibet – 260kt), Sarcheshmeh (400kt?), Cukaru Peki & Bor (200kt) although after these nothing much. And as with most markets, copper trading has been financialised (and automated) and speculators seem to have had their fun with copper for now: See this by Andy Home today: https://www.mining.com/web/home-fund-managers-give-copper-a-wide-berth-as-china-cools/ – Frik